Karate as a Sport, Do, & Jutsu

In my study of Karate, I have had the opportunity to study under several Sensei and with a great many more advanced martial artists, each of whom has brought their own strengths and style to the exercise. When it comes to the more philosophical side of the art, however, much of my understanding has been influenced by books. It is study of these sources that causes me to wonder if a large portion of our "advanced" practitioners may, in fact, have very poor Karate - regardless of the quality of their spinning ura-mawashe-geri.

In this monograph, I propose to examine the changing meaning of Karate in three technical forms, as a Sport, a Do, and a Jutsu. In so doing, I plan to follow and extend the division outlined by Damon Young (D. Young - "Pleased to Beat You" in Priest & Young - Martial Arts & Philosophy) and accept that the soundest functional translation of the Japanese term "jutsu" denotes technical mastery of a craft or body of knowledge. Hence Karate-Jutsu would simply be the art of fighting using Karate as a body of knowledge and a training base. Do, influenced by Taoism, has strong relations to our term ethos, and therefore Karate-Do is to combine the technical aspects of Karate-Jutsu with a philosophical and ethical programme for self improvement (though without losing the jutsu aspect). Karate-Sport is the extension term I propose for those who study Karate, and yet are neither fighters nor philosophers.

I will finally argue that Karate-Sport has its own system of values, different and distinct from Karate-Jutsu & Karate-Do, and that recognising these differences will allow Karateka to engage in more honest discussions about what they are teaching or studying, why they are doing it, and what value they think it is to others to learn it. Whilst I will admit quite openly that I have little interest in Sport Karate, I do not think that this should be used as a pejorative term, for it is in many respects a development and improvement of the art, and my main motivation is not to berate, but to identify an epistemic difference so that where gaps are occurring in the teaching of the art (jutsu) it is easier to identify what is being lost, why, and whether and how to correct it.

In this monograph, I propose to examine the changing meaning of Karate in three technical forms, as a Sport, a Do, and a Jutsu. In so doing, I plan to follow and extend the division outlined by Damon Young (D. Young - "Pleased to Beat You" in Priest & Young - Martial Arts & Philosophy) and accept that the soundest functional translation of the Japanese term "jutsu" denotes technical mastery of a craft or body of knowledge. Hence Karate-Jutsu would simply be the art of fighting using Karate as a body of knowledge and a training base. Do, influenced by Taoism, has strong relations to our term ethos, and therefore Karate-Do is to combine the technical aspects of Karate-Jutsu with a philosophical and ethical programme for self improvement (though without losing the jutsu aspect). Karate-Sport is the extension term I propose for those who study Karate, and yet are neither fighters nor philosophers.

I will finally argue that Karate-Sport has its own system of values, different and distinct from Karate-Jutsu & Karate-Do, and that recognising these differences will allow Karateka to engage in more honest discussions about what they are teaching or studying, why they are doing it, and what value they think it is to others to learn it. Whilst I will admit quite openly that I have little interest in Sport Karate, I do not think that this should be used as a pejorative term, for it is in many respects a development and improvement of the art, and my main motivation is not to berate, but to identify an epistemic difference so that where gaps are occurring in the teaching of the art (jutsu) it is easier to identify what is being lost, why, and whether and how to correct it.

All Karate is a Solution to a Problem

Allow me to provide a little context. Karate was not invented in a vacuum. No martial art is. The exact history of the art is at best mysterious and at worst lost to the sands of time, however there are a few general points of agreement:

1) Karate comes from Okinawa

2) It was developed on Okinawa from a number of influences, but most notably Chinese Gung-fu. (Also including Tegumi, Aiki-Daito-Ryu Jujutsu, indigenous Okinawan striking systems, and possibly Muay Boran)

3) It has been indelibly associated with eastern philosophy, even before the contributions of Gichin Funakoshi. The survival of Kata such as Jion, supposedly named for the Jionji temple (H. Kanazawa - Karate: The Complete Kata), and the nominal survival of groups such as the Shorinji-Kan ("place of the Shaolin Temple") indicate a connection with Buddhist temples.

It is traditionally believed, at least in the West, that Karate was developed as a response to the invasion of Okinawa (then the Rykyu Kingdom) by the Samurai. This is unlikely to be true; firstly given that Karate is a striking based art and that Samurai tended to wear armour. Most battlefield systems that deal with armoured opponents utilise grappling in order to disable the opponent or to set up a killing blow - Karate does have these elements, however the balance is all wrong for the assumption that one's foe is armoured. Secondly, the invasion of the Ryukyu Kingdom was resolved quite quickly. The Rykyu King, Sho Nei, did not wish to waste his men's lives, and after the capture of Shuri Castle in 1609 the Rykyu Kingdom became a vassal state to Japan.

There are stories of Karate warriors taking on local Samurai, however these tend to have the hallmarks of folk tales rather than authentic history, with the Karate warrior rescuing a damsel in distress, or oppressed villagers. Whilst it would be impossible to say that such things did not happen, I think it is reasonable to assumer they were, at worst, isolated cases.

Generally, the relationship between Okinawa and Japan seems to have been quite harmonious. In 1639 Japan closed its doors to the outside world for two and a half centuries when it adopted the Sakoku policy. The vassal state of Okinawa would have done likewise, were it not also a vassal state of China for reasons of trade. This provided a back door for trade between Japan and the rest of the world, and helped to keep the Okinawan port of Naha very busy.

Gichin Funakoshi grew up during the Meiji restoration of 1868, and in his Karate-Do: My Way of Life, he several times mentions encounters with local toughs in Okinawa. He relates tales of robbery, drunken assault and gang violence both as he experienced them personally, and as they were experienced by his mentors, Anko Asato & Anko Itosu. What is noticeable is that all of the events Funakoshi relates were of civilian violence. There was no suggestion of Karate being a battlefield art in his time, nor that it was used against oppressive Samurai.

Given this information, I would suggest that Karate was developed in an unstable civil environment rather than a hostile military one. Okinawa between 1609 and 1868 was an international port of some importance, and would have been host to contingents of sailors on shore leave around coastal towns. Inland, whether through unemployment, idleness, or some form of oppression, there appears to have been enough civic disturbance to keep the practitioners of Karate busy. This combination of circumstances more than explains why people may have felt the need to develop a fighting system - any why it appears to be one targeted at unarmoured individuals - potentially those who attack in groups. (Do not forget, Jujutsu, a battlefield system, can afford to assume a 1-on-1 approach because you are likely to have other soldiers with you at the time)

The historical data combines with the technical styling of Karate to suggest that this fighting system was designed as a form of civic combat, to protect the individual from violent criminal aggressions.

When the Problem Changes, the Nature of the Karate Changes

Of course when Japan opened its borders and restored the Emperor Meiji, Okinawa would have become less important as an international port. This might explain why it was around this time that Anko Itosu began to teach Karate in schools - developing the Pinan/Heian series of Kata as a suitable exercise and self defence programme for school children.

The traditional explanation offered had been that the study of Karate was banned in Okinawa until 1868. However just because a ban is lifted does not mean that the formerly-banned-thing would take on a popular mantle, which is precisely what appears to have happened. I think there may be another pressure at play. If one were studying a combat art, primarily to defend against unruly sailors, and then a change in circumstances meant that those sailors were no longer around, would there still be a need to study the combat art?

I suspect what may have happened is that there was a decrease in local pressures to learn Karate, both due to the opening up of trade and the improving administration of the islands, and the response from teachers - simply to ensure the survival of the art - was to evolve it into another context.

It was a civil servant named Shintaro Ogawa who formalised the decision to include Karate in the Okinawan school system. After seeing a demonstration af Gichin Funakoshi's school, which was in turn based on the material being taught by Itosu, he was impressed and wrote a formalised report to the local government (Gichin Funakoshi - Karate Do: My Way of Life). The virtues of karate as a form of self defence, a means of instilling discipline, and physical exercise were noted, and it seems that these bases formed the planks upon which a new, socially driven, Karate could be built.

Shortly afterwards, around 1912, Gichin Funakoshi gave a demonstration of the art to men of the Japanese Navy. This appears to be the first time in modern history that Karate intersected with the military (who saw immediate application), again suggesting that prior to this time it was a purely civilian pursuit.

Broadly put, this is when a new type of Karate can be said to become prevalent. There is no doubt in my mind that the great masters of Karate had been practising a Taoist form of the art long before this time (Funakoshi himself notes that most of his teacher were great scholars of the Chinese classics, and in the stories he relates they show great ethical character), however this focus on Karate as a "way of life" - as opposed to " a tool to stop people assaulting you" - becomes the foremost element in the art around the turn of the twentieth century. It is this different/ciation that provides the philosophical basis for what we now call "Karate-Do".

This transition was aided by Funakoshi's own scholarship. A schoolmaster, Funakoshi was also familiar with the Chinese classics, and this influence can be found throughout his work. Throughout Karate-Do: My Way of Life, there are constant themes of learning from one's experiences, seeking to do the ethical thing, and seeking to eliminate the illusion of the self (all central tenets of Buddhist philosophy, particularly the last one). Karate Do Kyohan closes with a reflection on the meaning of Budo; much is made of the fact that the ideograph for the idea means "to stop halberds", and this reflection invites the reader to reflect on how training shapes character. Likewise, Funakoshi's "Twenty Precepts" and "Dojo-Kun" are philosophical codes for modern warriors, broken into bitesize and repeatable chunks so that they can be learned in a Dojo environment. The main influence suggested both by Funakoshi's thought and his relative paucity appears to be Zen Buddhism, though another possibility is that he kept his philosophy brief out of a teacher's habit of engaging the audience (as opposed to the philosophers habit of bewildering them).

In essence, what is evident over the period from c.1900-c.1930 is that Karate undergoes a change in image. This is largely led by Gichin Funakoshi, who spread the art to a wider Japanese audience during this period. (It was also influenced by his friendship with Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo). This change in image is likely to be a retreat from justification by proximal to ultimate causation. That is, as the immediate need to learn a way of fighting died down, other reasons for studying Karate had to be found, and the easiest place to find them was in the most advanced practitioners. Advanced practitioners like Funakoshi and Itosu saw Karate as a being much wider mental and physical discipline which could be practised across all aspects of ones life, so as the proximal need to learn how to fight declined this projection of Karate as a system of moral and spiritual development came to be the main reason people were encouraged to study it.

This may sound silly at first, particularly to those who are most concerned with the act of fighting, however it does bear scrutiny. In no way was the fighting technique of the art compromised by this repositioning, it simply ceased to be the most important part (remember Funakoshi's 5th pinricple; variously translated as "Spirit first, Technique Second" or "Mentality over Technique"). And one should also bear in mind that the traditional way of teaching Karate had not involved sparring as we would understand it. Funakoshi tells us he devoted himself ten years just to learning Kata (the three Tekki or Naihanchi forms), and only introduced Kumite training drills once he moved to Japan (Gichin Funakoshi - Karate-Do Kyohan) because several of his students had also studied Kenjutsu and were used to participating in shiai or contests. Funakoshi saw the benefit of this method of training but was careful to warn us "it must be emphasised that sparring does not exist apart from the kata but for the practice of kata... When one becomes enthusiastic about sparring, there is a tendency for his kata to become bad".

So, whilst the focus may have shifted from Jutsu (the technical aspects of Karate) to Do (the ethical and philosophical aspects) there was, in fact, more fighting going on in classes than there had been before.

Has the problem changed again?

Funakoshi may have been very prescient to forewarn against taking sparring too seriously, or divorcing it from the study of kata. I would argue that we have potentially entered a new phase of development; moving from Karate-Do in the first half of the twentieth century towards Karate-Sport as the century progressed into the new Millennium.

The fact that there are now infinitely more Karate competitions, both in Europe and globally, than there were 70 years ago is not evidence that there has been a change in ethos, which is the claim I am making. It is simply evidence that more people are training in and learning karate, and that more hobbyists are treating that study recreationally. These things could all be true whilst maintaining an ethos of Do or even Jutsu. What must be evident in order to suggest a transition away from Do is three things

1) The over-development of sporting techniques relative to the other aspects of Karate study (such as self defence, biomechanics, anatomy, and self discipline)

2) The loss of knowledge amongst senior practitioners of certain technical (jutsu) elements of fighting.

3) The inability of Karateka to spar with, and exchange ideas with, other martial artists and styles.

The first point cannot be clearly demonstrated except by long and detailed study, which I unfortunately do not have the resources to do at this time. I shall simply say that I have observed enough clubs where this is true that I think a more in depth study ought to be carried out, and I suspect that there will be a substantial number of Dojo which fit the bill.

The second and third points are more easily demonstrated, and so it is to these we now turn. We find evidence of point (2) as early as 1938, when Kenwa Mabuni stated:

Funakoshi may have been very prescient to forewarn against taking sparring too seriously, or divorcing it from the study of kata. I would argue that we have potentially entered a new phase of development; moving from Karate-Do in the first half of the twentieth century towards Karate-Sport as the century progressed into the new Millennium.

The fact that there are now infinitely more Karate competitions, both in Europe and globally, than there were 70 years ago is not evidence that there has been a change in ethos, which is the claim I am making. It is simply evidence that more people are training in and learning karate, and that more hobbyists are treating that study recreationally. These things could all be true whilst maintaining an ethos of Do or even Jutsu. What must be evident in order to suggest a transition away from Do is three things

1) The over-development of sporting techniques relative to the other aspects of Karate study (such as self defence, biomechanics, anatomy, and self discipline)

2) The loss of knowledge amongst senior practitioners of certain technical (jutsu) elements of fighting.

3) The inability of Karateka to spar with, and exchange ideas with, other martial artists and styles.

The first point cannot be clearly demonstrated except by long and detailed study, which I unfortunately do not have the resources to do at this time. I shall simply say that I have observed enough clubs where this is true that I think a more in depth study ought to be carried out, and I suspect that there will be a substantial number of Dojo which fit the bill.

The second and third points are more easily demonstrated, and so it is to these we now turn. We find evidence of point (2) as early as 1938, when Kenwa Mabuni stated:

"The Karate that has been introduced to Tokyo is actually just a part of the whole. The fact that those who have learnt Karate there feel it only consists of kicks and punches, and that throws and locks are only to be found in Judo or Jujutsu can only be put down to a lack of understanding... Those who are thinking of the future of Karate should have an open mind and strive to study the complete art."

Gichin Funakoshi hints at a similar concern in the 1957 preface to the 2nd edition of Karate-Do Kyohan;

"As a result of the social disorder that followed the end of World War II, the Karate world was dispersed, as were many other things, Quite apart from a decline in the level of technique during these times, I cannot deny that there were moments at which I came to be painfully aware of the almost unrecognisable spiritual state to which the Karate world had come from that that had prevailed at the time I had first introduced and begun the teaching of Karate."

Later in the same book, Funakoshi tells us:

"... in Karate, hitting, thrusting, and kicking are not the only methods; throwing techniques and pressure against the joints are also included... it is not always necessary to use powerful techniques like hitting, thrusting, and kicking, but, adjusting to the situation, softer techniques such as throwing may be used, and in this versatility there is an inexpressible savour. ... All these techniques should be studied, referring to basic kata."

We even have pictoral evidence of Funakoshi demonstrating throwing and joint locking techniques, and there is evidence that there were more practised and waiting to be rediscovered in kata.

To put it simply; Gichin funakoshi thought that if you are not studying throws as part of your kata, then you are missing something out from your Karate practice. As Funakoshi is one of the strongest links to the traditional art, and one of it's most revered masters, I am willing to bend to the argument from authority (a move I seldom make) and agree that it is so.

There are obviously other elements to kata, but ask yourself - when was the last time you studied a kata in depth? Learning how to deploy the moves as an integrated system of combat? Who were you supposedly defending yourself from, and how were you supposedly doing it? Did you understand the moves, and could you apply them in a live situation? Were you thinking of fighting, or just kicking and punching? Was your bunkai perfunctory, or was it a vital part of your study?

The unfortunate truth appears to be that bunkai is seldom practised seriously in most karate clubs. Personally, I find this odd, because to my mind bunkai is the ultimate purpose of karate - as well as the road to mastering the art.

Try thinking of karate like any other subject. There are certain key texts, in our case kata, that one must be familiar with to be considered fluent in the subject. In the case of Shotokan, there are 26 kata, some styles may have more, some have less, however they all serve the same purpose. They are texts to be studied. Understanding what they say is key to learning how to use them.

In philosophy, people are still trying to develop ideas based on the writings of Plato, who wrote two and a half Millennia ago. More importantly, they are still finding new ways to read the texts he left behind and gaining new insights from re-reading them. Likewise in theology; Christians have a limited number of texts in the Bible, but are constantly shedding new light on old writings through diligent study. This is even more so the case in science, where we are discovering new texts and new ways to read old texts all the time. The nature of mathematics had not changed, but our ability to apply it to new situations is leading to the potential for things like nuclear fusion and more manageable space travel. At the other end of the spectrum, we are only just beginning to discover how to "read" genetic material, and the potential horizons for new discovery are being pushed back on an almost monthly basis.

The apex of these fields is research - looking at the subject matter, combining it in new ways or with new problems, and advancing knowledge in the field. Close behind is teaching, which is largely aimed to give students enough skills in research to be able to conduct their own research.

Yet I know of very few dojo that could be considered a "research" environment. Students tend not to be asked to solve problems or study bunkai intensively. (There are a few exceptions that spring to mind, however these are - to my knowledge - an acute minority). They are taught to learn the kata, to perform the kata, and ... that's the endpoint. To be able to perform the kata for the sake of performing the kata. I know that certain kata are now a requirement for a grading syllabus, but surely the requirement should be that the student has studied the kata and can apply the knowledge and principles it contains, rather than whether they can perform it by rote? If a person walked into a physics exam having memorised every formula known to man, but was unable to apply them to solve the problems set before him we would regard him as the most useless specimen of a physicist ever known - so why do we treat our kataany differently?

And in case it appear I am going too far, it may be worth sharing a snippet from Funakoshi's "Karate-Do; My way of Life":

You may train for a long time, but if you merely move your hand and feet and jump up and down like a puppet, learning Karate is not very different from learning a dance. You will never have reached the heart of the matter; you will have failed to grasp the quintessence of Karate.

Gichin Funakoshi hints at a similar concern in the 1957 preface to the 2nd edition of Karate-Do Kyohan;

"As a result of the social disorder that followed the end of World War II, the Karate world was dispersed, as were many other things, Quite apart from a decline in the level of technique during these times, I cannot deny that there were moments at which I came to be painfully aware of the almost unrecognisable spiritual state to which the Karate world had come from that that had prevailed at the time I had first introduced and begun the teaching of Karate."

Later in the same book, Funakoshi tells us:

"... in Karate, hitting, thrusting, and kicking are not the only methods; throwing techniques and pressure against the joints are also included... it is not always necessary to use powerful techniques like hitting, thrusting, and kicking, but, adjusting to the situation, softer techniques such as throwing may be used, and in this versatility there is an inexpressible savour. ... All these techniques should be studied, referring to basic kata."

We even have pictoral evidence of Funakoshi demonstrating throwing and joint locking techniques, and there is evidence that there were more practised and waiting to be rediscovered in kata.

To put it simply; Gichin funakoshi thought that if you are not studying throws as part of your kata, then you are missing something out from your Karate practice. As Funakoshi is one of the strongest links to the traditional art, and one of it's most revered masters, I am willing to bend to the argument from authority (a move I seldom make) and agree that it is so.

There are obviously other elements to kata, but ask yourself - when was the last time you studied a kata in depth? Learning how to deploy the moves as an integrated system of combat? Who were you supposedly defending yourself from, and how were you supposedly doing it? Did you understand the moves, and could you apply them in a live situation? Were you thinking of fighting, or just kicking and punching? Was your bunkai perfunctory, or was it a vital part of your study?

The unfortunate truth appears to be that bunkai is seldom practised seriously in most karate clubs. Personally, I find this odd, because to my mind bunkai is the ultimate purpose of karate - as well as the road to mastering the art.

Try thinking of karate like any other subject. There are certain key texts, in our case kata, that one must be familiar with to be considered fluent in the subject. In the case of Shotokan, there are 26 kata, some styles may have more, some have less, however they all serve the same purpose. They are texts to be studied. Understanding what they say is key to learning how to use them.

In philosophy, people are still trying to develop ideas based on the writings of Plato, who wrote two and a half Millennia ago. More importantly, they are still finding new ways to read the texts he left behind and gaining new insights from re-reading them. Likewise in theology; Christians have a limited number of texts in the Bible, but are constantly shedding new light on old writings through diligent study. This is even more so the case in science, where we are discovering new texts and new ways to read old texts all the time. The nature of mathematics had not changed, but our ability to apply it to new situations is leading to the potential for things like nuclear fusion and more manageable space travel. At the other end of the spectrum, we are only just beginning to discover how to "read" genetic material, and the potential horizons for new discovery are being pushed back on an almost monthly basis.

The apex of these fields is research - looking at the subject matter, combining it in new ways or with new problems, and advancing knowledge in the field. Close behind is teaching, which is largely aimed to give students enough skills in research to be able to conduct their own research.

Yet I know of very few dojo that could be considered a "research" environment. Students tend not to be asked to solve problems or study bunkai intensively. (There are a few exceptions that spring to mind, however these are - to my knowledge - an acute minority). They are taught to learn the kata, to perform the kata, and ... that's the endpoint. To be able to perform the kata for the sake of performing the kata. I know that certain kata are now a requirement for a grading syllabus, but surely the requirement should be that the student has studied the kata and can apply the knowledge and principles it contains, rather than whether they can perform it by rote? If a person walked into a physics exam having memorised every formula known to man, but was unable to apply them to solve the problems set before him we would regard him as the most useless specimen of a physicist ever known - so why do we treat our kataany differently?

And in case it appear I am going too far, it may be worth sharing a snippet from Funakoshi's "Karate-Do; My way of Life":

You may train for a long time, but if you merely move your hand and feet and jump up and down like a puppet, learning Karate is not very different from learning a dance. You will never have reached the heart of the matter; you will have failed to grasp the quintessence of Karate.

So, there is documentary evidence from the masters which suggests that we, as modern practitioners, have lost a substantial portion of their art due to things not being practised or passed down properly. But I think there may me more compelling circumstantial evidence; how many throws and joint locks can you find in Bassai-Dai? Could you use the Tekki/Naihanchi kata in a ground fighting situation? What are the hops for at the end of Chinte?

If we truly knew our kata, these questions would pose no problem. Unfortunately, I think a substantial portion of use would - if we were being honest - have to admit that these are not questions we can answer readily.

And this leads me to the third condition which would indicate a movement away from "Karate-Do"; the inability to spar with and exchange ideas with other martial artists.

In the mists of Karate history, we know that exchanging ides with other martial artist must have occurred, because we know that karate has several sources, including Gung-fu and tegumi. The melding of these styles into karate could not have happened without practitioners of one style engaging with and learning from practitioners of the others. More recently Gichin Funakoshi formed a friendship with Jigoro Kano which impacted the teaching of both arts (Kano developing Judo kata to include some Funakoshi inspired striking, and Funakoshi refining his philosophy to me more in line with Kano's), and is even reputed to have trained with him for some time. More significantly, Hironori Otsuka, founder of Wado Ryu Karate, created his style after blending elements of Shotokan Karate with traditional Japanese Jujutsu. This exchange of ideas, particularly amongst senior practitioners, not only helped to cement their legacy as legendary martial artists, but made the martial arts scene as we know it today.

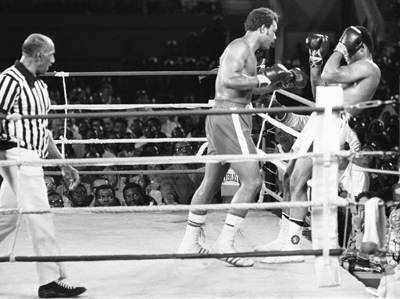

Unfortunately, more recent examples are not so easy to find. Iain Abernethy, who is said to be the world's foremost expert on practical bunkai, is one. But few others stand out, even where they should. The popularity of the UFC and the rise of mixed martial arts competition should be a blessing to Karateka; an organised and relatively safe forum to practice technique and learn from opponents of different styles is an opportunity previous generations could only have dreamed of. Karate, however, seems to be under represented in the sport of MMA.

There have been some prominent practitioners; Bas Rutten, Chuck Liddell, Georges St. Pierre & Lyoto Machida, but when compared to the hundreds of boxers, Muay Thai fighters, wrestlers and BJJ fighters it seems like small fry. Especially when considering that Bas relied as much on his Muay Thai, and has now eschewed Karate in favour of Krav Maga, Chuck relied mostly on his boxing and wrestling abilities, and Georges & Lyoto both have reputations as being relatively boring fighters (i.e. they tend to win "decision" victories rather than finish their opponents with strikes or submissions).

An early example of a Karateka who was open to this new venue was Fred Ettish. In 1994 Fred was called in as a replacement fighter at UFC 2. The fight, as described by one internet commentator:

He faced Johnny Rhodes, a doughy but tough kickboxer. The bell rings and Ettish strikes a pose. He throws a snap kick... It hits exactly where he threw it and he, Johnny Rhodes, and the people watching from home all say the same thing: oh shit. A guy who trains with nine year olds at the YMCA is in a real fight.

Fred Ettish was dominated for three minutes and seven seconds before being choked out Johnny, whose expertise was listed as "streetfighter". It was an embarrassing match.

(As an aside, Fred should get ten out of ten for his approach after the match. He learned from the experience, upped his martial arts game and is now a highly proficient martial artist in several styles, though he still teaches karate. In 2009 a 53 year old Ettish took his second professional MMA fight and emerged with a convincing victory after forcing his opponent to tap. This is a man who, to my mind, embodies the ethos of Karate-Do. After all, anybody can fail, but not everybody is willing to learn from it.)

There could be many reasons why one doesn't want to compete in professional MMA. Lack of time, fitness, injuries and so on could all be good reasons as to why Karateka are not flocking to the sport en masse, and prefer the relatively comfortable confines of Kumite tournaments. But that does not explain why Kumite is not being adapted to involved a more MMA type element - or why we continue to neglect those elements in our training.

If nothing else, televised UFC events should have sent a message to all traditional martial artists - learn to fight on the ground; you cannot always guarantee you will be standing in a fight. If you are training for self defense, it seems only logical that you would train from the worst case scenarios; such as being knocked over or pinned down. Yet most of the Karateka whom I know seem unwilling to work these features into their training. Partly because it's never been done before (it has, just not by people in your lifetime) and partly because "it's not really karate" (it is; just not a part of it you know).

The reticence to engage with MMA, which is the closest we are likely to come to an objective test of "real" fighting without entering into morally abhorrent territory (For a full examination of the problem of knowledge in Martial Arts, see: Gillian Russell - Epistemic Viciousness in the Martial Arts) is baffling. Most clubs are taking few, if any, steps to address groundwork, grappling, or getting grabbed and instead appear to be focusing on the three K's, Kihon, Kata, and Kumite.

A New Problem: The Focus on Kumite

I hope the evidence outlined above, has convinced the reader that the "problems" we are addressing in Karate have moved on. Traditionally, the problem was was one of self defence, for which our main tool was the study of Kata. This, as I have outlined above, we tend no longer to do effectively. In the twentieth century, the problem was re-emphasised to be one of personal development. This, I believe, has been narrowed to one particular type of development, and that is linked to the growth in sport Kumite and sport-Karate.

The self development inherent in sporting competition comes to us from the public school ethos of the late Victorian period. Healthy competition can drive people to improve their techniques, work harder, become fitter and, hopefully, become better Karateka for doing that. On the other hand, unhealthy competition can lead to gamesmanship - playing the rules to maximum advantage without regard for the spirit of the game.

In some ways this can be actively hurtful; Rory Miller (in Meditations on Violence) relates the story of a friend, a prison guard, who was assaulted by a criminal. The guard,being a Karate expert, evades the attack and launches three punches in return. They all land with a loud snap on said criminals chest, doing absolutely no damage. Whether the story is true or not (and it has many variations) it illustrates the point that training solely for Kumite can get in the way of fighting. Given that Karate is fundamentally a fighting system I would argue that should be viewed as a problem - anything we do in training should be designed to make us better at fighting, not worse!

This can be nowhere better demonstrated than in developing habits or techniques which rely entirely on the rules of Kumite competition for their effectiveness. Take, for example Aghayev Vs. Smaal at last year's European Karate Championships. Both of these men had adopted a stance that begs the question; "how practical can that be?". Each man fought sideways on in an extended kiba-dachi. All movement had to come from bouncing and shuffling which, to their credit, they managed to achieve and make look easy (I can assure you, it isn't). Firstly, fighting sideways on may have the advantage of presenting a smaller target, but it also leaves half of your weapons trailing behind. (Personally, I side with Bas Rutten on this and prefer to be close to square on, so I can throw more techniques.) Secondly, this side-alignment robbed their kicks of much of their power. In a points based Kumite environment that may not be an issue, however for self defence throwing a weak kick is almost universally a bad idea. Thirdly, nobody moves around the world through stylised shimmying. It's just not practical, so my understanding is that this is a technique that was developed to give an edge in the competition. Fourth, the stance they have adopted appears to assume the opponent will not throw leg kicks. In Kumite, they cannot. I would be interested to see a Muay Thai or MMA fighter try that stance. Perhaps worst of all, when they closed, all aggression ceased. Neither showed any real inclination towards preventing clinching or takedowns, knowing that the referee would separate them.

These techniques and strategies are, at least in some clubs, being taught as the proper way to perform a technique. Tommy Morris (in Karate: the complete course) includes the following advice in a section on "getting your scores seen":

"Don't use the shorter range variants (of the roundhouse kick) which impact with the ball of the foot because this configuration... (slows) the kick right down."

"Lean away from the kick to take your body out of the line of counter attacks"

At another point in the book he counsels;

"From the scoring point of view it is not a good idea to use more than three techniques in any combination... with a melee of arms and legs flying about it becomes very difficult for the referee to distinguish what is and what is not a scoring technique."

I would not wish to imply that Morris is a bad Karateka (after all, there is plenty of evidence to suggest the opposite), however it is clear that his practise and teaching have been heavily influenced by the rules of Kumite competition. The advice he gives, whilst good for point sparring, is actively harmful for self defence, and in that sense I would argue it poses a threat to Karate as an art. It is quite one thing to vary a technique for competition for reasons of athletics or safety, it is quite another to change the technique and forget its original purpose.

Kumite and Do; Finding Focus

It should not be understood that I am opposed to Kumite or competition, quite the opposite is true. I am, however, opposed to "teaching to the exam". The purpose of studying Karate is to learn Karate, not to learn how to perform a menu of tricks.

If the focus of one's training becomes Kumite, at the expense of studying the Do & Jutsu aspects of Karate, then one will perennially be seeking an edge on the competition. How to kick higher or faster, with little regard as to whether the technique is becoming more effective (for the true test of effectiveness is in causing injury to an opponent if necessary). This puts the focus on the self in relation to others, which is contrary to the aim of "perfection of character" which Funakoshi thought was the ultimate purpose of all Karate. The focus on the self in Karate should never be in relation to another self, it should be in relation to one's own previous self. Is your technique better now than it was yesterday? Are you working harder now than you were last week? Do you feel more in control than you did last year?

These are the fundamental questions we are trying to answer every time we enter a Dojo. Kumite can be a part of that, insofar as it gives us recognisable goals to work towards, achievements, motivation and enjoyment. However it has to be understood that Kumite, or sport Karate, is only one small aspect of the art, and that if it is taken out of this context then what is being taught cannot be the Karate that masters like Funakoshi wished to hand down.

As such, I would suggest there should be several types of Kumite used in training (and I owe this idea to Iain Abernethy, who I believe does this in his club); as well as the standard kickboxing style that we are all used to, why not also include Kumite which just uses hand techniques, kumite with just kicks, kumite with only grappling, kumite where one person is a striker and the other a grappler (to practise takedown defense), kumite where one karateka starts on the ground and has to fight back to his or her feet? The possibilities in this sense are endless, and using these ideas would help form Karateka as well rounded martial artists.

Using Kumite as a proving ground for one's skills is not only admirable, I would argue it is necessary in order to advance as a martial artist, but not at the expense of actually studying the art. As such, I think the easiest solution is to identify what type of Karate is being taught, so that students know what they are learning, why they are learning it, and can put that knowledge into context in their own study.

Conclusion

Most clubs will be able to teach all three elements of Karate, however asking people to identify what they are doing and why they are doing it (reflective pedagogy) will help to highlight gaps in instructors knowledge, so that they can take steps to address these gaps, and will be more aware of their own abilities when it comes to teaching their students.

In writing this monograph, I have highlighted three distinct ethos (ethodes?) within the world of Karate, and given some historical context to each of them. Further, I have argued that these ethos have advanced progressively from each other, and that they represent developments in the modern art of Karate. I have, however, raised concerns about over-developing any one aspect of the art relative to its history and functionality, and set out the case that the modern focus on Kumite competitions is showing signs of doing just that - to the possible detriment of the art.

Moving from Jutsu, or the technical aspects of Karate, to Do - the much broader notion of a "way" of Karate represented a significant shift in focus, however this change in pedagogical emphasis did not fundamentally alter what Karate is or was. In order for Sport Karate to have a similar effect we, as practitioners, require to be aware of the essence of Karate, and use sport to augment that essence - not to substitute for it. If done properly, the sport form of Karate can build upon the Jutsu and Do forms, preserving the art for the next generation as well as providing a forum for practitioners to improve their skills. If done poorly, focusing on sport can distort what Karate is to the point where understanding is lost, and nothing but the game will survive.

In order to prevent that, it is not enough for advanced practitioners to be merely technically proficient Karateka, they must also be scholars. They must have an understanding of the history and philosophy behind the art as it stands, enough knowledge of contemporary matters to allow them to read Kata as texts for self defence and combat, and the creativity to search for new bunkai and adapt the principles contained in kata for the situations people face in the modern world.

The first step in that process is recognising what type of Karate we are teaching and learning, and having the objectivity to ask whether we have departed from the way outlined for us by past masters. If we are to change something, that should always be a conscious selection; something done for a known and planned reason. It should never be allowed to happen through an elision of tradition caused by ignorance, complacency, and the fetishising of superficial victories over perfection of character.

Fred Ettish was dominated for three minutes and seven seconds before being choked out Johnny, whose expertise was listed as "streetfighter". It was an embarrassing match.

(As an aside, Fred should get ten out of ten for his approach after the match. He learned from the experience, upped his martial arts game and is now a highly proficient martial artist in several styles, though he still teaches karate. In 2009 a 53 year old Ettish took his second professional MMA fight and emerged with a convincing victory after forcing his opponent to tap. This is a man who, to my mind, embodies the ethos of Karate-Do. After all, anybody can fail, but not everybody is willing to learn from it.)

There could be many reasons why one doesn't want to compete in professional MMA. Lack of time, fitness, injuries and so on could all be good reasons as to why Karateka are not flocking to the sport en masse, and prefer the relatively comfortable confines of Kumite tournaments. But that does not explain why Kumite is not being adapted to involved a more MMA type element - or why we continue to neglect those elements in our training.

If nothing else, televised UFC events should have sent a message to all traditional martial artists - learn to fight on the ground; you cannot always guarantee you will be standing in a fight. If you are training for self defense, it seems only logical that you would train from the worst case scenarios; such as being knocked over or pinned down. Yet most of the Karateka whom I know seem unwilling to work these features into their training. Partly because it's never been done before (it has, just not by people in your lifetime) and partly because "it's not really karate" (it is; just not a part of it you know).

The reticence to engage with MMA, which is the closest we are likely to come to an objective test of "real" fighting without entering into morally abhorrent territory (For a full examination of the problem of knowledge in Martial Arts, see: Gillian Russell - Epistemic Viciousness in the Martial Arts) is baffling. Most clubs are taking few, if any, steps to address groundwork, grappling, or getting grabbed and instead appear to be focusing on the three K's, Kihon, Kata, and Kumite.

A New Problem: The Focus on Kumite

I hope the evidence outlined above, has convinced the reader that the "problems" we are addressing in Karate have moved on. Traditionally, the problem was was one of self defence, for which our main tool was the study of Kata. This, as I have outlined above, we tend no longer to do effectively. In the twentieth century, the problem was re-emphasised to be one of personal development. This, I believe, has been narrowed to one particular type of development, and that is linked to the growth in sport Kumite and sport-Karate.

The self development inherent in sporting competition comes to us from the public school ethos of the late Victorian period. Healthy competition can drive people to improve their techniques, work harder, become fitter and, hopefully, become better Karateka for doing that. On the other hand, unhealthy competition can lead to gamesmanship - playing the rules to maximum advantage without regard for the spirit of the game.

In some ways this can be actively hurtful; Rory Miller (in Meditations on Violence) relates the story of a friend, a prison guard, who was assaulted by a criminal. The guard,being a Karate expert, evades the attack and launches three punches in return. They all land with a loud snap on said criminals chest, doing absolutely no damage. Whether the story is true or not (and it has many variations) it illustrates the point that training solely for Kumite can get in the way of fighting. Given that Karate is fundamentally a fighting system I would argue that should be viewed as a problem - anything we do in training should be designed to make us better at fighting, not worse!

This can be nowhere better demonstrated than in developing habits or techniques which rely entirely on the rules of Kumite competition for their effectiveness. Take, for example Aghayev Vs. Smaal at last year's European Karate Championships. Both of these men had adopted a stance that begs the question; "how practical can that be?". Each man fought sideways on in an extended kiba-dachi. All movement had to come from bouncing and shuffling which, to their credit, they managed to achieve and make look easy (I can assure you, it isn't). Firstly, fighting sideways on may have the advantage of presenting a smaller target, but it also leaves half of your weapons trailing behind. (Personally, I side with Bas Rutten on this and prefer to be close to square on, so I can throw more techniques.) Secondly, this side-alignment robbed their kicks of much of their power. In a points based Kumite environment that may not be an issue, however for self defence throwing a weak kick is almost universally a bad idea. Thirdly, nobody moves around the world through stylised shimmying. It's just not practical, so my understanding is that this is a technique that was developed to give an edge in the competition. Fourth, the stance they have adopted appears to assume the opponent will not throw leg kicks. In Kumite, they cannot. I would be interested to see a Muay Thai or MMA fighter try that stance. Perhaps worst of all, when they closed, all aggression ceased. Neither showed any real inclination towards preventing clinching or takedowns, knowing that the referee would separate them.

These techniques and strategies are, at least in some clubs, being taught as the proper way to perform a technique. Tommy Morris (in Karate: the complete course) includes the following advice in a section on "getting your scores seen":

"Don't use the shorter range variants (of the roundhouse kick) which impact with the ball of the foot because this configuration... (slows) the kick right down."

"Lean away from the kick to take your body out of the line of counter attacks"

At another point in the book he counsels;

"From the scoring point of view it is not a good idea to use more than three techniques in any combination... with a melee of arms and legs flying about it becomes very difficult for the referee to distinguish what is and what is not a scoring technique."

I would not wish to imply that Morris is a bad Karateka (after all, there is plenty of evidence to suggest the opposite), however it is clear that his practise and teaching have been heavily influenced by the rules of Kumite competition. The advice he gives, whilst good for point sparring, is actively harmful for self defence, and in that sense I would argue it poses a threat to Karate as an art. It is quite one thing to vary a technique for competition for reasons of athletics or safety, it is quite another to change the technique and forget its original purpose.

Kumite and Do; Finding Focus

It should not be understood that I am opposed to Kumite or competition, quite the opposite is true. I am, however, opposed to "teaching to the exam". The purpose of studying Karate is to learn Karate, not to learn how to perform a menu of tricks.

If the focus of one's training becomes Kumite, at the expense of studying the Do & Jutsu aspects of Karate, then one will perennially be seeking an edge on the competition. How to kick higher or faster, with little regard as to whether the technique is becoming more effective (for the true test of effectiveness is in causing injury to an opponent if necessary). This puts the focus on the self in relation to others, which is contrary to the aim of "perfection of character" which Funakoshi thought was the ultimate purpose of all Karate. The focus on the self in Karate should never be in relation to another self, it should be in relation to one's own previous self. Is your technique better now than it was yesterday? Are you working harder now than you were last week? Do you feel more in control than you did last year?

These are the fundamental questions we are trying to answer every time we enter a Dojo. Kumite can be a part of that, insofar as it gives us recognisable goals to work towards, achievements, motivation and enjoyment. However it has to be understood that Kumite, or sport Karate, is only one small aspect of the art, and that if it is taken out of this context then what is being taught cannot be the Karate that masters like Funakoshi wished to hand down.

As such, I would suggest there should be several types of Kumite used in training (and I owe this idea to Iain Abernethy, who I believe does this in his club); as well as the standard kickboxing style that we are all used to, why not also include Kumite which just uses hand techniques, kumite with just kicks, kumite with only grappling, kumite where one person is a striker and the other a grappler (to practise takedown defense), kumite where one karateka starts on the ground and has to fight back to his or her feet? The possibilities in this sense are endless, and using these ideas would help form Karateka as well rounded martial artists.

Using Kumite as a proving ground for one's skills is not only admirable, I would argue it is necessary in order to advance as a martial artist, but not at the expense of actually studying the art. As such, I think the easiest solution is to identify what type of Karate is being taught, so that students know what they are learning, why they are learning it, and can put that knowledge into context in their own study.

Conclusion

Most clubs will be able to teach all three elements of Karate, however asking people to identify what they are doing and why they are doing it (reflective pedagogy) will help to highlight gaps in instructors knowledge, so that they can take steps to address these gaps, and will be more aware of their own abilities when it comes to teaching their students.

In writing this monograph, I have highlighted three distinct ethos (ethodes?) within the world of Karate, and given some historical context to each of them. Further, I have argued that these ethos have advanced progressively from each other, and that they represent developments in the modern art of Karate. I have, however, raised concerns about over-developing any one aspect of the art relative to its history and functionality, and set out the case that the modern focus on Kumite competitions is showing signs of doing just that - to the possible detriment of the art.

Moving from Jutsu, or the technical aspects of Karate, to Do - the much broader notion of a "way" of Karate represented a significant shift in focus, however this change in pedagogical emphasis did not fundamentally alter what Karate is or was. In order for Sport Karate to have a similar effect we, as practitioners, require to be aware of the essence of Karate, and use sport to augment that essence - not to substitute for it. If done properly, the sport form of Karate can build upon the Jutsu and Do forms, preserving the art for the next generation as well as providing a forum for practitioners to improve their skills. If done poorly, focusing on sport can distort what Karate is to the point where understanding is lost, and nothing but the game will survive.

In order to prevent that, it is not enough for advanced practitioners to be merely technically proficient Karateka, they must also be scholars. They must have an understanding of the history and philosophy behind the art as it stands, enough knowledge of contemporary matters to allow them to read Kata as texts for self defence and combat, and the creativity to search for new bunkai and adapt the principles contained in kata for the situations people face in the modern world.

The first step in that process is recognising what type of Karate we are teaching and learning, and having the objectivity to ask whether we have departed from the way outlined for us by past masters. If we are to change something, that should always be a conscious selection; something done for a known and planned reason. It should never be allowed to happen through an elision of tradition caused by ignorance, complacency, and the fetishising of superficial victories over perfection of character.