Self Defense and the use of Improvised Weapons

I like weapons. Not in a serial killer-y way, but as a practising martial artist I think they are great fun. They are a good way to vary training and develop additional strength and dexterity. The thing is, because I like socialising with normal people, I tend not to carry these practise weapons round with me; which means I’m training for what exactly? The night somebody crashes into our dojo during nunchuck class they are going to be sorry, but otherwise I can’t think of a reason why I would learn to use them for “self defense”. I have had to admit, these weapons are for training and history purposes only. But looking into that history a little more closely has helped me realise some things about using weapons for self defense.

As some of you may know, my weapon of choice is the staff. I have invested a fair amount of time and energy learning to do complicated and intricate spins and combinations with this weapon. The thing is, I know that all of that is for fun – as my Sensei keeps reminding me “it’s just a big stick”. The way we train to actually fight with the weapon looks incredibly different from virtually all of the exercise drills we do with it because, at the end of the day, we’re really just trying to thump somebody very hard with a big stick. Everything else is for show and exercise. I think this happens a lot. If you enjoy training with a weapon you end up putting effort into making it look cool, and lose sight of the fact that it was originally used for fighting. Probably unintentionally. A huge amount of the most fetishised weapons in the martial arts were originally improvised from whatever happened to be at hand when the viking/mongol/pillager burst into your house.

Nunchaku

Let’s start with that internet favourite – Nunchaku (or “nunchucks” as people insist on calling them). I remember watching an episode of the Simpsons as a Child (the one where Bart pretended to learn Karate, in case anybody is interested), and noticing a background joke; a documentary entitled “Nunchucks: Cool but Useless!”. This is pretty much the most accurate summary of nunchaku I’ve come across. (Disclaimer; I still practise with nunchaku – I’m just not under the impression they would be my first choice of weapon). If you practise with nunchaku, you can look incredibly cool. People like Bruce Lee did it, people like Jake Mace try and help you to do it too. Most of us, unfortunately, end up looking more like this guy. He’s no novice, there’s a bit of practice behind him, but he still ends up doing more harm to himself than anybody else. Even experienced martial artists who spar with these weapons look like they are having an advanced slap fight.

The point is not that nunchaku are not effective, but that they are not effective in the way that we think they are. That dynamic there is why no professional soldier has ever used nunchaku as a primary weapon. Ever. Can you imagine the chaos of hundreds of men flailing at each other – mostly impotently – for hours on end? The fancy stuff we do for fun and exercise does not translate to the weapon’s practical use, and the room needed to wield the weapon effectively make fighting in formation impossible.

Plus, the flail – our equivalent of nunchaku – was a peasant weapon in Europe. There are no known paintings of Louis XIV holding a flail, but a peasant fending off an armed trooper (above)? Or a group of peasants in revolt? They had flails. Not because flails were super effective, but because they were the most effective things to hand that one could use. The flail is an agricultural instrument. It was used for threshing; separating wheat from chaff. If you were a European peasant called to go to war, or to a peasants revolt, or – as is the case above – who needed to defend yourself from a lone dandy, it was a handy thing to have around because it was big and could hit things very hard. It was a much better plan than going to war expecting to bite the enemy to death, so if you didn’t have a sword, spear or crossbow, you could grab your flail and turn up to the fight. It may not surprise you to learn that nunchaku had a very similar origin. They are nothing more mystical than rice flails. And they served the same purpose. While nunchaku do appear in several Asian martial art forms, not least kung fu, they are best known for their use in Karate, an Okinawan art. Here, the use of this farming implement was encouraged after the Japanese invaded the Rykyu kingdom and made the island nation of Okinawa part of Japan. Owning weapons of war was banned, however owning agricultural tools was necessary to eat, so there were plenty lying around. And if some Samurai invader decided to stick his Katana wielding nose in your business? You had two options; pray for a merciful beheading or pick up the nearest heavy thing and try to brain him with it.

I think that is where nunchaku would be valuable, as weapons of self defense. They are the sort of thing an Okinawan peasant would have lying around, and they pack the punch to take down an attacker, whether he be a criminal or a Samurai invader. Those are really the two most important things in a weapon of self defense; can it hurt my attacker? and is it there when I need it?. They have they additional advantage of articulation. A simple stick or baton works to multiply the force of your strike, but the rope or chain in nunchaku accelerates the striking arm much faster than the handle and this really improves the level of force your strikes land with. Nunchaku have virtually no defensive capability at all. You cannot block, parry or cover with them. But these capabilities are more important in a longer engagement, such as a battle – where shields were popular for covering and absorbing blows, or even in a more ritualised format, such as a duel – where both antagonists would parry for their own protection and work to take advantage of openings.

Recent research (Darin Waugh, Real Fighting – Real Facts, 2013) suggests that most self-defence encounters last around a minute. Also, they are frantic, and since you would tend to be on the back foot, your first priority is not to establish a solid defence but to create a counter attack, and preferably do enough damage to escape or win. Therefore, for the limited scenario of self-defence nunchaku are a good choice of weapon. Partly because they can hit very hard but mostly because they were right there when you needed them. This is going to be a common theme amongst our treatment of improvised weapons. Since most attacks are a surprise to the victim, a super cool weapon that is really effective but that needs retrieved from a hiding spot and/or assembled is less than no good for self defence. While you are trying to remember where you left that self cocking crossbow with the night vision sniper scope your attacker has all the opportunity he needs to beat you to a pulp or worse.

Recent research (Darin Waugh, Real Fighting – Real Facts, 2013) suggests that most self-defence encounters last around a minute. Also, they are frantic, and since you would tend to be on the back foot, your first priority is not to establish a solid defence but to create a counter attack, and preferably do enough damage to escape or win. Therefore, for the limited scenario of self-defence nunchaku are a good choice of weapon. Partly because they can hit very hard but mostly because they were right there when you needed them. This is going to be a common theme amongst our treatment of improvised weapons. Since most attacks are a surprise to the victim, a super cool weapon that is really effective but that needs retrieved from a hiding spot and/or assembled is less than no good for self defence. While you are trying to remember where you left that self cocking crossbow with the night vision sniper scope your attacker has all the opportunity he needs to beat you to a pulp or worse.

The Tonfa

The Tonfa (or Tunqua) is a side handled baton.

Straight off the bat, this is a slightly more practical weapon than nunchacku. Lacking the articulation it packs slightly less punch, but is far easier to control, which is why it is favoured as a less lethal weapon by some security professionals. It can be wielded in a manner similar to a regular baton or stick weapon, but has the advantages of also being wielded with the side handle facing outwards (“hammer grip”) to give a smaller area of impact and thus magnify the effective force of the weapon, or defensively, using the side handle (“shield grip”).

However, despite its versatility and effectiveness for law enforcement and security professionals, the tonfa was never designed as a weapon, and it has never seen much military use. The humble origins of this weapons lie in another piece of Okinawan agriculture – folklore has it that the tonfa was derived from a quern handle (or a crutch). But we have one huge clue with the tonfa that should immediately tell us we are dealing with a weapon for self defence (as opposed to battlefield) use. Dual Wielding. It was not done on the battlefield, however it was sometimes done in duelling. It is definitely practised with the tonfa (at least if you study Kobudo). While training one tends to hold both Tonfa in the same grip, either a “sword”, “shield” or “hammer” style of dual wielding. Through experimentation I have come to enjoy using one tonfa in a shield grip and another in a hammer grip, finding this to be quite a practical combination – though not very flash. While maybe I would carry one of these around for enforcement or self protection (pretty much as police officers do) I would think carrying two would be unnecessary and cumbersome. The most logical explanations are that we train with them in pairs to build ambidexterity, and would only ever use one; but if that were effective then those police who use side handle batons would adopt the training method, and they don’t. Instead they learn how to integrate their free hand to use grappling and apply controls or restraints. The other explanation, and the one that I prefer, is that some sword wielding samurai bursts through the front door of your house, and you grab the nearest things to try and brain him with. I can absolutely see tonfa being used in pairs against an armed attacker who surprises you.

Horsebench

The horsebench is another example of the “heavy things that you can hit someone with an a pinch” genre. A popular form of traditional seating in China, it certainly has a history of being wielded in bar fights.

The Horse bench is very poor offensively, slow, clumsy and relatively low impact, it isn’t a very good weapon. It’s sheer size, however, makes it a surprisingly effective improvised shield, and it still has the advantage of increasing one’s reach and minimising risk to one’s person. The horsebench has been adopted into several styles of kung fu and wushu, and now has dozens, if not hundreds, of forms.

Note the large, deflective movements and the short choppy strikes. These would suggest that the bench was envisioned being used against swinging weapons (e.g. Naginata, sabres or baseball bats) rather than thrusting ones (e.g. spears, rapiers or knives). That is not to say, however, that the horsebench would be useless against these weapons, simply that the techniques we see in horsebench forms were not designed with them in mind. Our next entry demonstrates another line of thinking.

Chair

In WW2 W.E. Fairbairn encouraged us all to “get tough”, and suggested that should a soldier ever have to fight a man armed with a knife, he should follow the example set by the horsebench and grab his chair to defend himself.

Fairbairn gives the rather optimistic estimate that using a chair against a knife you should have the odds c. 3-1 in your favour. If this were true then more armies would issue their soldier with battle chairs rather than bayonets, however the general principle is sound. The chair is a shield, creating distance, and jabbing it into an attacker creates opportunities either to disarm, disable or escape. I would certainly prefer to bring a chair to a knife fight than nothing at all.

Cane/Walking Stick

Around the turn of the twentieth century a number of systems of self defence appeared utilising the cane or the walking stick. The most famous of these was Bartitsu, an eclectic blend of Boxing, Jiu-Jitsu, Savate and stick fighting.

However, Bartitsu was far from alone. Pierre Vigny taught canne de combat, a variant of cane fencing at his school of arms in Paris, and later became an instructor at the Bartitsu club. In 1923 H.G. Lang, an officer in the Indian police, released an entire book on the subject called The “Walking Stick” Method of Self Defense. The idea behind all of these uses was not that the cane was the ultimate weapon, but that it had the potential to be a weapon if needed, and it was something most gentlemen had on them most of the time. Similar ideas were applied to umbrellas and parasols, which the practitioners of these forms were quite open about being inferior quality sticks. To quote Neo-Bartitsu instructor Marc Donnelly “Is this a good weapon? It is if it’s in my hand when I’m attacked”.

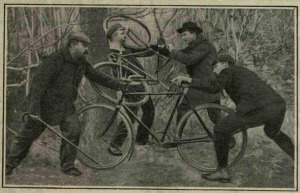

Bicycle

The images above, printed in Italian Magazine La Stampa Sportiva in 1904, suggest using a bicycle as a shield or a battering ram in the event of having to fend off footpads. These suggestions appear to have been quite serious. As the victorian cyclist has already pointed out, conflict between pedestrians and cyclists appears to have been a serious problem – and from my reading it seems most likely that gangs of toughs saw cyclists as soft targets either for sport or mugging. The response from self-defense enthused bicycle riders appears to have been to weaponise their velocipede.

Swords/Pistols

This entry is bound to be a little controversial. Up until now, everything mentioned in this article was purposed for something else, and has found use as a weapon under some peculiar circumstance. Swords and pistols are designed with being a weapon in mind. My argument, however, is that swords and pistols should primarily be considered civilian weapons – or at the very least equal parts civilian and military. Throughout most of military history both swords and pistols have been side arms. In Japan, the preferred weapon until the late 16th century was the Yari, and it was only after the battle of Sekigahara in 1600 ushered in the Tokugawa Shogunate that theKatana began to be preferred. It should be noted that after 1600 the main type of combat a Samurai was likely to encounter was duelling rather than battling. Similarly, in Medieval Europe polearms (poll axes, halberds, bardiches, glaives, spears etc.) prevailed on the battlefield, however the culture of duelling with swords lasted until the beginning of the nineteenth century (See R. Shoemaker – Male Honour and the Decline of Public Violence in Eighteenth Century London). Nobody in the 1800’s was suggesting they settle differences with a pollaxe, but this was not because a pollaxe is an inferior weapon to a sword, but because the sword achieved a crossover into civilian life as a fashion accessory and status symbol. It was a side arm – convenient to wear and therefore easy to take with you. This made it more useful for self defence than battlefield weapons like the pollaxe because it was on your hip. The pollaxe would have been a pain to carry around – and so you would have left it at home.

An eighteenth century flintlock pistol. Note the brass plating on the handle, to reinforce it for use as a clubbing melee weapon.

Likewise the pistol. Flintlock pistols were pretty hopeless as weapons. Smooth bore and short barrelled, their accuracy left a huge amount to be desired. Excepting a brief period where the caracole (ride horse into pistol range, shoot, run away, reload, repeat) was in battlefield use, pistols have never been primary weapons for soldiers. They have, however, been used for duelling, as personal protection, and as side arms for developing forces, like the police. Police in England could, and often did, carry pistols until 1896 – although this was often an officer’s personal choice rather than official policy. Police forces in America and Europe still carry pistols as standard. Again, the point is that a pistol is small enough to be easy to carry; and officers like the police are not expected to need weapons in the course of their normal duties.

What all of these weapons have in common is convenience. If they were particularly effective as weapons they would be front line use for military personnel, because those are the people who need the best weapons. For everybody else, be they private individuals or police, they do not need the most weapon-y weapons, they need the most convenient ones – because most of the time they are not using them, and hopefully they will never have to.

Realistically, my conclusion to this has to be that most weapons are actually pretty useless at self defense. And that most of the things we think of as self defense tools are pretty useless as weapons. What it comes down to is one simple question; is this likely to be in arms reach when I am being attacked? If the answer is “no” then it will be no good at self defense.

Some of this approach, however, can be more effective than others:

No comments:

Post a Comment